Process Schedulers in Operating System

Contents

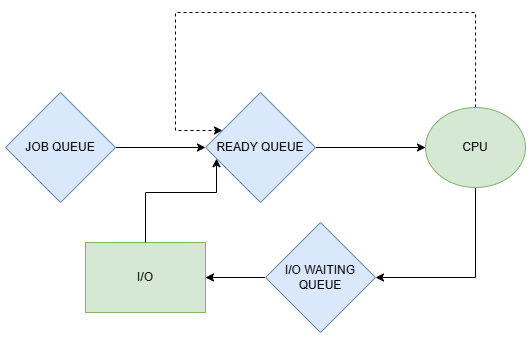

ToggleProcess schedulers are the parts of the OS that handle the nitty-gritty of deciding and switching processes. They work in layers to control everything from which jobs enter the system to who grabs the CPU in the moment. The main ones are long-term, short-term, and medium-term schedulers, each with a specific job to keep the flow smooth. They use queues—like job queues for new arrivals or ready queues for waiting processes—to organize and pick based on rules like priority or arrival time.

Schedulers run frequently (short-term ones every few milliseconds) to adapt to changes, saving and restoring process details during switches to avoid data loss. Overall, they ensure the system doesn’t waste cycles idling or get bogged down by unfair picks.

What is Process Scheduling?

Process scheduling is the way the operating system decides which running program or process gets to use the CPU next and for how long. It’s like picking who speaks next in a meeting full of people with ideas; without it, everything grinds to a halt as processes compete for the limited CPU time. The goal is to keep the CPU busy, make the system responsive, and use resources fairly, especially in setups where multiple processes share the machine.

Types of Process Schedulers

There are three main types of process schedulers, each focusing on different levels of management.

Long-Term Scheduler (Job Scheduler): This one decides which new processes from the job queue get admitted into the ready queue and loaded into memory. It controls the overall number of active processes to avoid overwhelming the system, balancing CPU-heavy and I/O-heavy jobs for steady performance. It runs infrequently, like when a user submits a batch, and aims for a mix that keeps utilization high without overload.

Short-Term Scheduler (CPU Scheduler): Picks the next process from the ready queue to run on the CPU, often every time slice or interrupt. It’s fast and frequent, using algorithms to select based on priorities, fairness, or deadlines, then dispatches it via context switching. This directly affects how snappy the system feels, minimizing wait times for interactive tasks.

Medium-Term Scheduler (Swapper): Handles swapping processes in and out of memory when RAM is tight, removing suspended ones to disk and bringing others back later. It reduces the active process count temporarily to free space, running when memory pressure builds, and helps in systems with variable loads by pausing non-urgent tasks without killing them.

Think of a busy railway station during festival rush for long-term scheduling: The ticket counter (scheduler) doesn’t let every single traveller in at once; it picks groups based on train schedules and crowd size, admitting only what the platforms can handle to avoid chaos—mirroring how it balances process entry for stable system load.

For short-term scheduling, picture a roadside food stall with a single stove: The vendor (scheduler) switches between boiling milk, making tea, and serving biscuits in quick bursts, ensuring no customer waits too long while keeping the stall humming—much like picking processes to keep the CPU active and users happy without one order dominating.

Medium-term scheduling is like a school bus driver during peak hours: When the bus is full, the driver (scheduler) drops off kids at stops and picks up waiting ones, temporarily clearing space for smoother rides ahead—similar to swapping processes to disk, freeing memory for critical tasks until things ease up.