What are Scheduling Criteria in Operating System ?

Contents

ToggleScheduling criteria in operating system are the key metrics used to evaluate and choose CPU scheduling algorithms in operating systems.

They help measure how well an algorithm performs in terms of efficiency, fairness, and user experience, guiding the OS to balance competing goals like speed and resource use. By maximizing some (like utilization) and minimizing others (like waiting time), these criteria ensure the system runs smoothly without wasting CPU cycles or frustrating users with delays. Common ones focus on time-based measures and overall system health, with priorities sometimes added for critical tasks. Selecting algorithms based on these keeps multitasking effective, especially in busy environments like desktops or servers.

Main Scheduling Criteria

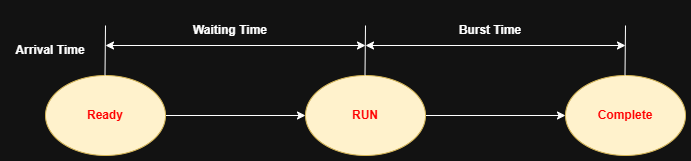

In CPU scheduling, arrival time, burst time, and completion time are fundamental metrics that help calculate performance like waiting and turnaround times. They form the basis for evaluating how well an algorithm handles processes, feeding into criteria like throughput and response time.

Arrival time marks when a process enters the ready queue, burst time is the CPU duration it needs, and completion time is when it finishes. These are inputs for simulations (e.g., Gantt charts) and outputs for analysis, often used in non-preemptive algorithms like FCFS where order matters.

- Arrival Time:The clock time when a process becomes ready for execution and joins the ready queue. It’s given as input for each process, showing when it arrives in the system (e.g., 0 ms for the first job). No formula needed—it’s predefined based on submission.

-

Burst Time (BT): The total CPU time a process requires to complete its execution, excluding I/O waits. It’s also an input, estimated or known for the process (e.g., 5 ms for a short task).

Completion Time (CT): The clock time when the process finishes its entire execution and exits the system. It’s calculated after simulating the schedule.

-

CPU Utilization: Measures how much of the CPU’s time is actually used for useful work, ideally keeping it busy from 40% (light load) to 90% (heavy) without overheating or idling. High utilization means fewer wasted cycles, but too much can cause slowdowns from overload.

-

Throughput: Counts the number of processes completed per unit time (e.g., jobs per hour), reflecting overall productivity. Higher throughput is better for batch systems, showing the scheduler packs more work efficiently without bottlenecks.

-

Turnaround Time: The total time from process submission to completion, including waiting, execution, and any I/O delays. It’s minimized to finish jobs quickly, important for users who want fast results on deadlines.

-

Waiting Time: The period a process spends in the ready queue, not including execution or I/O waits—just pure queuing. Lower waiting reduces frustration in interactive setups, preventing long lines of stalled tasks.

-

Response Time: Time from request submission to the first response (e.g., screen update), crucial for interactive apps like typing. Short response times make systems feel snappy, prioritizing user-facing tasks over batch ones.

Related Derived Metrics and Formulas

These build on AT, BT, and CT to assess scheduling efficiency:

-

Turnaround Time (TAT): Total time from arrival to completion, including waits and execution.

Formula: TAT=CT−AT -

Waiting Time (WT): Time spent in ready queue, excluding execution and I/O.

Formula: WT=TAT−BT or WT=CT−AT−BT -

Response Time (RT): Time from arrival to first CPU allocation.

Formula: RT= First execution start time −AT