Sequential Circuits

Contents

ToggleSequential circuits are digital logic circuits that holds past inputs to generate future outputs at any given point in time, unlike instant combinational circuits. They blend memory elements like flip-flops with gates, powering clocks, counters, and state machines in every computer and gadget.

Brief History of Sequential Circuits

Sequential logic roots trace to George Boole’s 1854 algebra, but Claude Shannon’s 1938 thesis applied it to relays for memory. Post-WWII vacuum tubes birthed flip-flops (1940s ENIAC counters). Transistors (1950s) shrank them; ICs (1960s) enabled synchronous designs with clocks.

By 1970s, Moore’s Law packed billions into chips—think Intel 4004’s registers. Today, FPGAs evolve them for AI. Evolution: Relay → Tube → Transistor → VLSI, from room-sized to pocket-sized.

What Are Sequential Circuits?

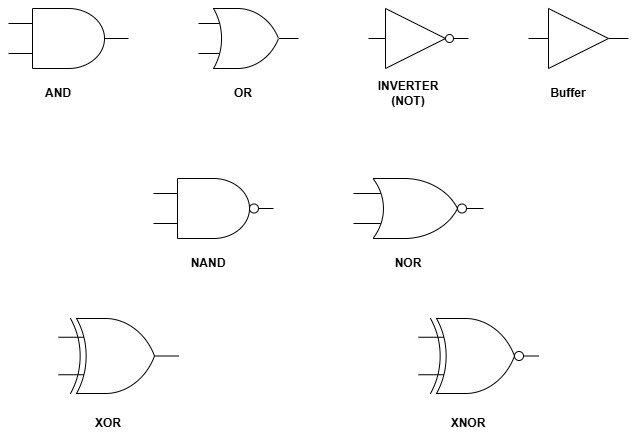

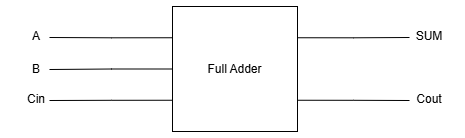

Sequential circuits output based on current inputs and previous states stored in memory (flip-flops/latches). Block: Combinational logic + feedback loop. Outputs evolve over time, unlike combinational’s “now-only” snap. Sequential Circuits are basically a set of combinational circuits which memory integrated inside to perform operations in a sequence.

Purpose of Sequential Circuits in Digital Design

Unlike combinational circuits, sequential circuits can remember past events, which allows them to handle tasks that change over time. They are used in many important areas:

1. State Tracking

Sequential circuits store the current “state” of a system. For example, a finite state machine (FSM) in a traffic light controller remembers whether the lights are currently green, yellow, or red, and switches to the next state based on time or sensors.

2. Counting and Timing

They can measure time or count events. Clocks, timers, and counters all use sequential logic to keep track of cycles or divide a high-frequency clock into slower signals.

3. Data Storage

Sequential circuits act as memory elements. Registers hold data temporarily, and shift registers move bits left or right—useful in communication, data loading, and arithmetic operations.

4. Control Logic

CPUs rely heavily on sequential circuits. They maintain the instruction cycle state (fetch → decode → execute → write-back) and control how each step happens in proper order.

Types of Sequential Circuits

Sequential splits into synchronous (clock-driven) and asynchronous (input-pulse).

Synchronous Sequential Circuits

Synchronous sequential circuits are systems where the memory elements update only when a clock edge occurs; either on the rising edge or the falling edge. Because everything changes in step with the clock, these circuits behave predictably and avoid glitches. Synchronization is achieved by a timing device called a clock pulse generator that produces a periodic train of clock pulses. These clock pulses are integrated in the system in such a way that the memory elements are affected only when the synchronization pulse arrives.

1. Flip-Flops

Flip-flops are edge-triggered, so they update only at the exact moment the clock toggles. They are the basic unit of storage.

Examples include JK, T, and D flip-flops.

-

A JK flip-flop can toggle between 0 and 1.

-

A T flip-flop always toggles when its input is 1.

-

A D flip-flop simply stores the input value at the clock edge.

2. Registers

Registers are groups of flip-flops combined to store multi-bit values—like the 32-bit Program Counter (PC) in a CPU.

They act as small, fast memory units inside digital systems.

3. Counters

Counters advance their stored value with each clock pulse.

-

Ripple counters update one flip-flop at a time (internal signals act asynchronously).

-

Synchronous counters update all flip-flops simultaneously, making them faster and more reliable.

Counters can be up, down, or modulo-N counters.

4. Shift Registers

Shift registers move data one bit at a time in a chosen direction.

-

SISO (Serial-In Serial-Out)

-

SIPO (Serial-In Parallel-Out)

They are commonly used in communication systems like UARTs, where data is transmitted serially.

Asynchronous Sequential Circuits

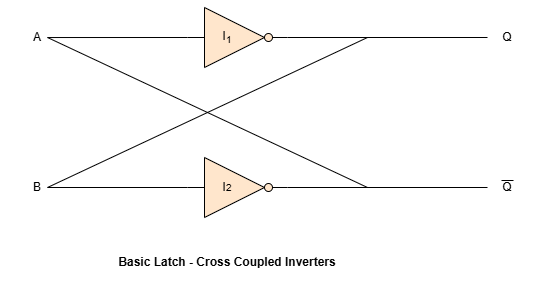

Asynchronous circuits operate without a clock. Their state changes happen immediately whenever an input changes. Because there is no clock to synchronize operations, they can be extremely fast—but also much more prone to glitches and timing problems.

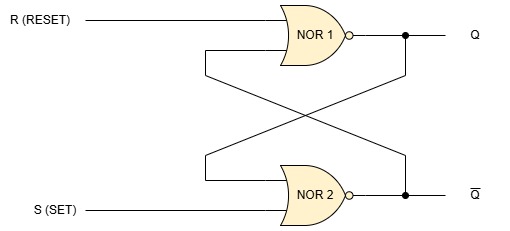

1. Latches

Latches are level-sensitive devices. They remain “open” or transparent while the clock is high, meaning the output follows the input. It is capable of storing 1 bit of information; 1 or 0. It has two inputs ; SET and RESET and two outputs that are complement to each other.

Common examples include SR latches and D latches.

Key Features

1. Direct Feedback

These circuits rely on immediate feedback paths.

Since nothing waits for a clock edge, even small changes in inputs can cause rapid state transitions.

2. No Clocked Flip-Flops

Asynchronous systems often use unclocked storage elements or rely entirely on gate feedback loops.

The state changes simply whenever signals propagate through the logic.

3. Ripple Behavior

Ripple counters are a classic example.

Each flip-flop’s output acts as the clock for the next one, causing the count to “ripple” through the chain asynchronously.

This makes them slower and more glitch-prone compared to synchronous counters.

Pros and Cons

Advantages

-

Extremely fast since there is no clock delay.

-

Useful for simple, small systems or specific tasks.

Disadvantages

-

Very hard to analyze and predict timing.

-

High risk of hazards, glitches, and metastability.

-

Not suitable for complex digital systems like CPUs.

Very precise explanation!!! 👍👍👍

Thankyou